The Jenkins-Birnie House at 59 smith A Hidden Charleston Treasure

In 2023, a new owner began the study and restoration of a federal period house

in Charleston’s historic Harleston Village neighborhood. Although this 206-year-

old dwelling was first restored in 1964 as a rental property by the preservationists

Elizabeth and Charles Woodward, it was conveyed eight years later to a family that

held the site until two years ago. The purchaser of 59 Smith Street assembled an

outstanding team including two architects and a historian/preservationist to

understand the documentary history of the property as well as to develop

restoration plans based on historic preservation guidelines.

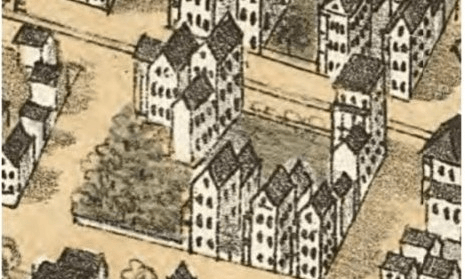

Plan of the City And Neck of Charleston, S.C. Reduced From Authentic Documents & Engraved By W. Keenan. Pub. Septr. 1844. The original Jenkins parcel is shown in red.

In 1786, the remaining heirs of Affra Harleston Coming, subdivided their tract

known as Harleston’s Pasture. In March 1818, Joseph Jenkins of Edisto Island

purchased the hitherto undeveloped lots 99 and lot 100 that had been part of this

division. In these first two decades of the nineteenth century, the earliest parcels

were being developed in what was then known as the Village of Harleston, with

substantial houses on large tracts.

Joseph Jenkins is best known for his purchase of an Edisto plantation from known

as “Brick House.” (the ruins of this early house built c. 1725 by Paul Hamilton,

survive). By 1822, “Joseph Jenkins planter” is recorded in the City Directory as

living on “Smith’s Lane.”

Brick House Ruins, Photographed by Thomas T. Waterman 1939, Historic American Buildings Survey, Library of Congress

In 1824 Joseph Jenkins sold the 2 lots and a dwelling house with outbuildings and

improvements to a cousin, Christopher Jenkins. The latter Jenkins was in

residence in the house by the next year and in keeping with the practice of the

wealthy planters of the Carolina lowcountry, he divided his time between this

dwelling and a plantation on John’s Island known as “Peaceful Retreat.”

Jenkins died in 1830.Only two of his five children survived past early childhood

Jenkins’ 1831 probate inventory, taken for both the Johns Island plantation and the townhouse on Smith Street, lists a number of enslaved people, some of them apparently living on this site, as well as possessions in the house, including values on certain furniture in the “Drawing Room” and “Parlour.”

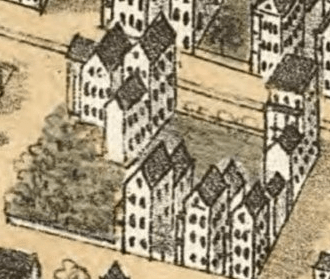

The 59 Smith parcel in 1852 from Bridgens and Allen, “An Original Map of Charleston, South Carolina”

When the property was to be sold in 1838, the advertisement described the

parcel: “A valuable lot of land, with an elegant dwelling house and all convenient

buildings thereon in good repair”

In the same year, a Master in Equity sale of the Smith Street lots resulted in the

conveyance of the Jenkins property to William Birnie (1782-1865). Birnie was a

Scottish immigrant from Aberdeenshire who arrived in Charleston in 1802. As

lead partner he built up the successful Birnie and Ogilvie hardware store on Broad

Street and served repeatedly as a director of the Bank of South Carolina, including

a long stint as its president.

Aside from the probable installation of gas lighting, the only definite alteration to

the interior of the house was the installation of the cast-iron, coal-burning

fireplace insert in the upstairs west chamber.

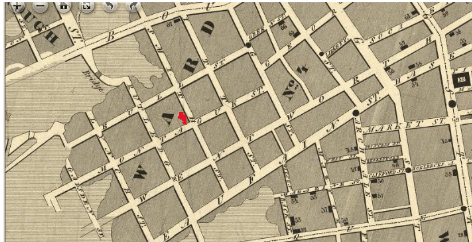

The 1872 Birdseye View of Charleston shows the house, its dependency, and a substantial fence enclosing a garden and an extensive grove of trees.

Birnie’s nephews from Aberdeen, William and James, lived in the

house in this period with their uncle William and his wife Mary Elizabeth

Birnie.. In 1865, William Birnie died on his estate in Greenville, a property he

had purchased in 1862 upon his departure from a Charleston soon to be

under siege. The house was briefly seized during the Union occupation but

restored to the family. No member of the Birnie family seems to have lived in

the house again and it became a rental property.

By 1875,the younger William Birnie, was listed as being a part of George Walton Williams’

mercantile firm and resident in New York City. Thereafter, the property was

rented to a succession of tenants. In 1886, the Charleston earthquake caused

little damage to the dwelling: only two collapsed chimneys, which were swiftly

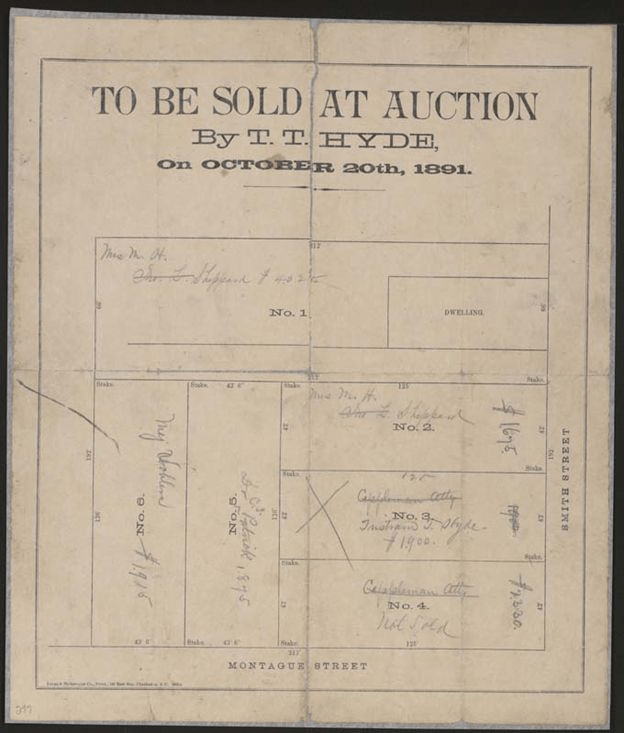

rebuilt. In 1891, the estate of the elder William Birnie was settled among his

heirs, and the Master in Equity ordered the sale of 59 Smith which was surveyed

for a subdivision into six lots.

On Left, July 1891 McCrady plat showing the parcel at northwest corner of Montagu and Smith divided into six lots. On Right, a printed plat dated October 20, 1891 advertising the auction sale of lots by T.T. Hyde

On Oct. 22,1891, John Black Leslie Birnie and the other heirs, conveyed Lot 1 to

Margaret Sheppard with “the large two and a half story Frame Dwelling on high

brick basement thereon with kitchen and other outbuildings” and also a small

parcel termed Lot 7 (which was incorporated into the rear of Lot 1).

From 1891 to 1931, the dwelling, generally known as the Sheppard House, served

as the residence of an extended family. John L. Sheppard, President of Carolina

Rice Company, lived here and by 1912, seven members of the Sheppard family

were listed at 59 Smith. In 1922, an interfamily transfer resulted in the house

being owned by William G. Sheppard and Daniel G. Sheppard. The house was

probably electrified at this time and a telephone installed. No other apparent

changes were made to the house’s interior during this ownership.

The extended Sheppard family occupied the property while operating their

business, the Carolina Rice Company. The Hurricane of 1911 with its destructive

effect on the industry undoubtedly affected their interests.

Measured drawings of the dining room mantel and the transom over the principal

entry from the piazza as well as other details appear in these works by the

Charleston-born Joseph Mordecai Hirschman who owned nearby 11 Montague

Street. Hirschman was a superbly trained architect in the New York firm of

Walker and Gillette. His obvious interest in Charleston buildings can be deduced

from the large number of his drawings surviving in the collection of the South

Carolina Historical Society.

59 Smith Street (House), Charleston, Charleston County, SC, 1940, Historic American Buildings Survey, Library of Congress

In 1931 William G. Sheppard conveyed 59 Smith to Jane Raisin, wife of the Rabbi

Jacob Raisin of K.K. Beth Elohim. Four years later, Mrs. Raisin converted the

house to apartments with four units in the main dwelling and two units in the

kitchen house. The major changes included the removal of the original staircase

in the house and an addition to the dependency. In 1940, a photographer for the

Historic American Buildings Survey photographed two views of the first floor, east

room. In the second image, a view through the window reveals the enclosure on

the piazza with a door accessing the stairs to the upstairs unit.

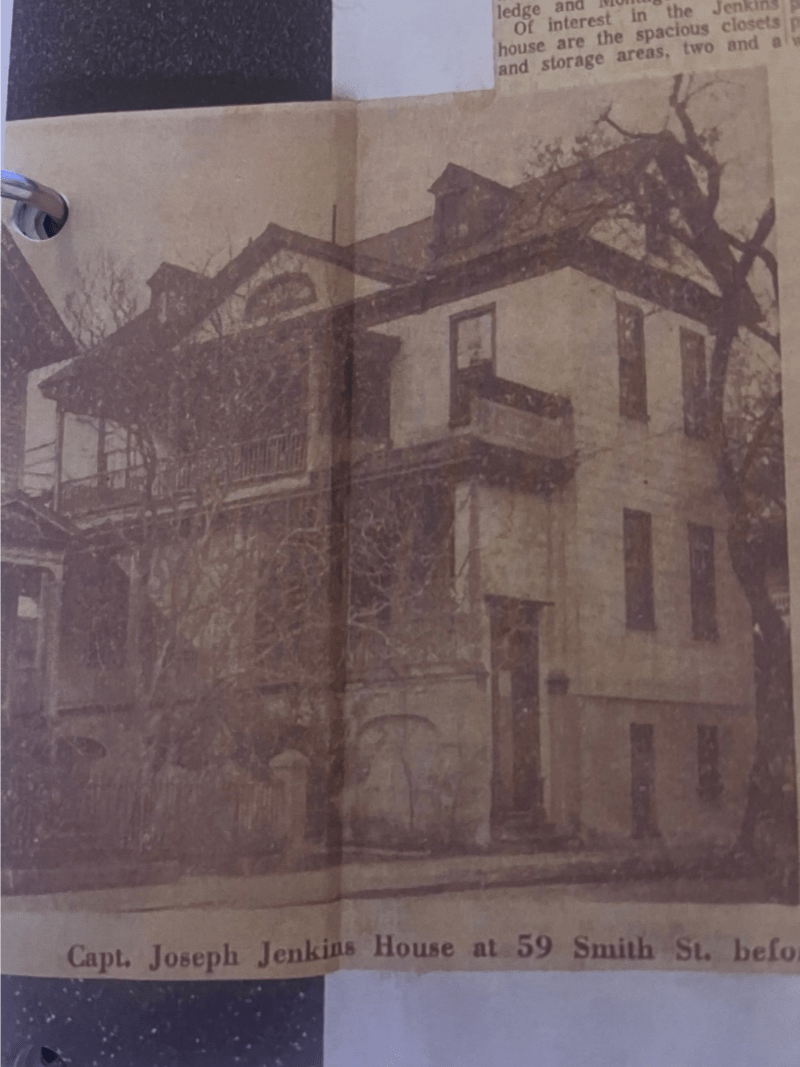

When the restoration was announced in the local press, the article used a photograph taken a few years earlier showing the impact of the alterations to the piazzas and the deteriorating state of the house at this point.

In January 1964, the Raisin heirs conveyed 59 Smith to Elizabeth Gadsden

Woodward of Charleston and Philadelphia.

The house had been described by the Raisin heirs in the listing as,

“Large 3 story frame dwelling arranged in 3 four room apartments with 2 story

brick 5 room

carriage house on the rear of deep lot. Property is in the need of repair. Sales

Price $ 12,500.”

Mrs. Woodward, and her husband Charles, were already prominent figures in the

nascent preservation movement in the lowcountry. Especially as major donors to

Historic Charleston Foundation, they spurred the Ansonborough Rehabilitation

Project beginning in 1958. On the other side of King Street, they personally

started the rejuvenation of Harleston Village. For their restoration of the I.

Jenkins Mikell House (the former Charleston County Library), and other projects,

the Woodwards chose Herbert De Costa of the H. A. De Costa Company and team

of traditional Charleston craftsmen in masonry, carpentry and ironwork. Patti

Foos Whitelaw, who served as decorative arts consultant to Historic Charleston

Foundation supervised the project at 59 smith,just as she did with several other such efforts of woodwards

Less than six months after the Woodwards’ January 1964 purchase of 59 Smith,

the restoration of the house as a single-family residence and the return of the

kitchen dependency to a single unit was fully complete.